Sara Dovre Wudali

The Invitation

We find the point of breaking by measuring tensile strength, by carrying all the burdens we can possibly carry. I broke at about -10 degrees in early February 2021. I was not going to step outside, not to grocery shop, not even to fill the birdfeeders. My family was going to survive off dry stores and vegetables with freezer burn until the winter was over.

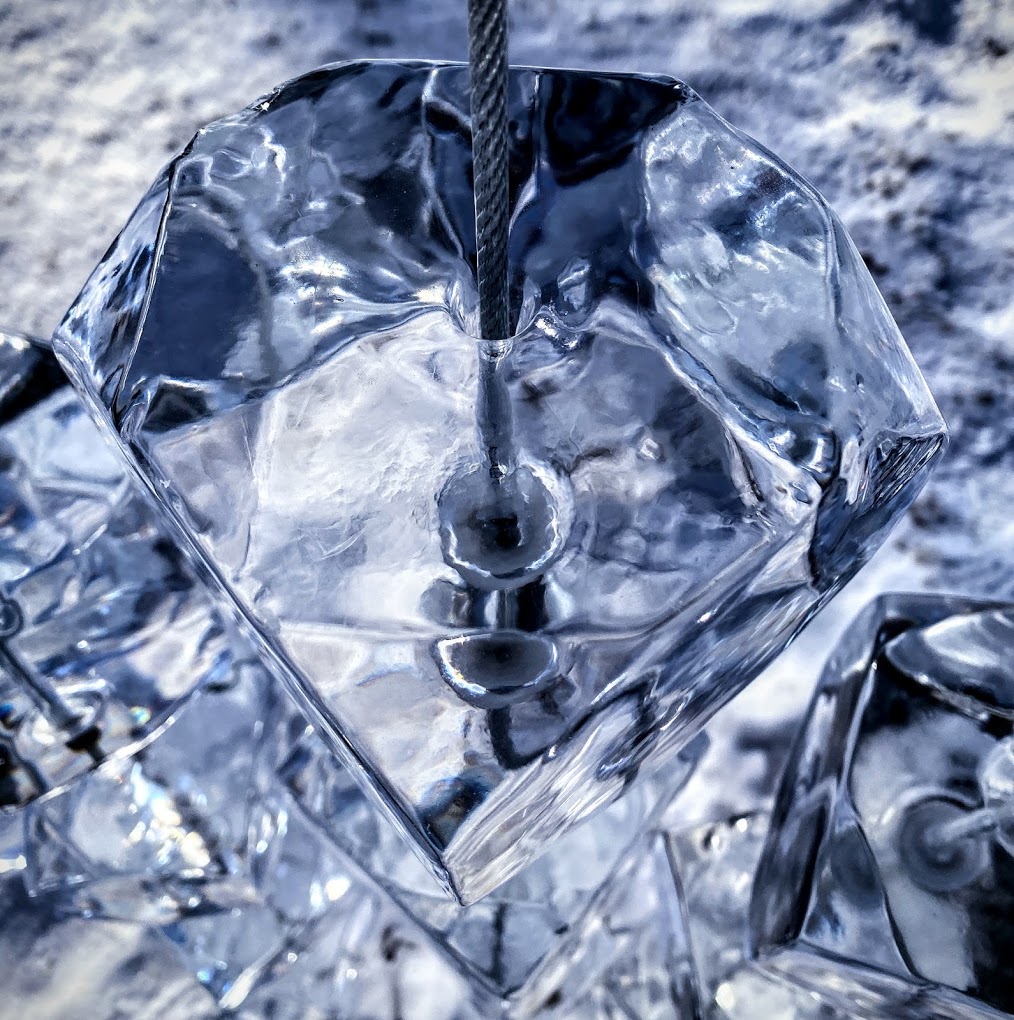

Then, the ice portal appeared in the median of Summit Avenue, a few blocks south of my house: a nine-foot sculptural arch with an opening to pass through, like a grand doorway, made of stark metal and the clearest pendants of hanging ice. The guerrilla art appeared as if by magic during the coldest days of the pandemic, and neighbors posted images online of snow-suited families visiting, crinkles around their eyes revealing the smiles hidden under scarves. These were the first happy pictures that I’d seen since Christmas card season. The ice drops in the photos were so crystalline and uniform that I wasn’t sure whether they were made of water or plastic. No one had taken off their gloves to check—people weren’t touching their own packages, let alone public art. I would have to go see for myself.

* * *

I hadn't always been afraid of the cold. A couple Januaries ago, I attended a women's wilderness retreat during a polar vortex. I was giddy with freedom from family responsibilities, as were my cabin mates, and plummeting temps were not going to freeze our spirits.

Guides taught us how to layer for afternoons in the woods when air temps had warmed up from the minus forties to the minus teens. Counselors showed us where the lake ice was safe to stand on and told us to blink more often to keep our eyeballs from freezing. We had instructions to park cars with their noses out, so that helpers could jump start them when batteries failed. Campers skied or snowshoed a half-mile to and from meals, and we wore hats and extra socks in our cabins because the heater couldn’t quite keep up. By the time I came home, I felt invincible. For the rest of the cold snap, while everyone in the city hid indoors, I pulled on my layers: wick, warmth, wind, and I skied tracks on the golf course by myself, a mini-wilderness experience in the heart of St. Paul.

* * *

My husband had been hit hard ten years earlier by H1N1, so when news started trickling in about a new, more virulent virus, I followed it closely. By the time the US began locking its doors in March 2020, I had already withdrawn cash, stocked the pantry and awaited the apocalypse. I quit my book club after one of the members, straight off an international flight, made fun of worriers like me by fake-coughing on the woman across the table. My daughter, a high school senior who was seeing germs instead of classmates in every social interaction, shrugged when I told her what had happened. “You don’t know how your friends are going to behave in a pandemic,” she said.

When the lockdown finally began, I closed our front door to the world with some relief.

* * *

The ice portal stood alone in semi-darkness, its frozen pendants lit red by the reflections of passing taillights. The city was silent, muffled by snow and the hat covering my ears. A slight breeze made the strings of ice drops sway as if they had just been gently touched by an invisible hand. As I got closer and my angle changed, the ice refracted the streetlights like warm candles in a chandelier. For the first time in a year, my head was silent; the running tally of R0-values and test positivity rates and statistics and maps were quiet. I heard only my breath, steady and fast after my walk, but slowing, slowing to match the gentle movement.

* * *

I had learned about germ-free bubbles in elementary school, seeing pictures of David, a boy whose immune system didn’t work. He played with a Fisher Price barn within the confines of a room-sized plastic bubble. His parents held his hand through the rubber gloves built into its walls. Scientific advances kept him happy, protected and smiling. Experience in my own metaphorical bubble tells me how carefully posed those photos must have been. A bubble is safe, sterile, and warm. You can paint your bathroom pink. You can try new recipes. But a bubble can also trap you inside staring vacantly at an open fridge.

And bubbles pop. Unhappy, David started poking holes in his bubble with a pin when he was four. Outside my bubble, the weather heated up and so did the world. Friends lost jobs. Launching children were trapped half in and half out of the nest. People walked alone into emergency rooms, lay alone in ICU beds. George Floyd was murdered, racism exposed so blatantly even white Minnesotans like me could not look away. The city burned. Helicopters circled endlessly. Cars without license plates sped through our neighborhood. Neighbors took shifts listening to the police scanner and walked up and down alleys looking for incendiaries. I took a night shift, knowing I wouldn’t be able to sleep, and watched the fires glow on the horizon to the north. It was the beginning of a pandemic summer, but I already longed for the fall freeze that would cool tempers.

* * *

The sculpture stood sentinel at the entrance to a snow-packed path lined with dormant lilac bushes. I considered its thing-ness: the black metal, the pristine ice. I lifted a metal rope, felt the heft. I listened to the soft puck, puck of one ice drop tapping another. The drops were frozen but hadn’t forgotten they were water. I tried to imagine how the artist had made over a hundred almost identical, soft-edged cubes. In my mind I saw a hand, red with cold, drilling holes through each cut block, perhaps dipping it in hot water to round edges. My curiosity overcame germophobia and I took my glove off and touched one, the air too cold for my heat to melt it.

* * *

I cried when I put my garden to bed in October. My daughter had decided she didn’t feel safe leaving home for college. My son hated his online university classes but wouldn’t visit home, worried he would infect us. My husband commuted to the attic instead of the suburbs. I had anticipated a quiet, empty nest to write in, but home was filled with people all day, every day. But not all the people. Not my parents, not my friends. Not graduation party guests. Not my choir. Not my book club. Why had I quit my book club?

After the first frost, I cut off the wilted canna lilies and dug out their tropical rhizomes. I dug like my grandma dug potatoes—turning the dirt, treasuring every single one. There were too many this year to keep, so I pulled together packages for friends and neighbors, each with a few bulbs and instructions for storage. I made contactless delivery to porches and stoops. I curled up the hose, turned off the outside water, and tucked my bulbs away, into the darkest, coldest corner of my basement, brown paper bags filled with hope.

* * *

I became still. Confined, I couldn’t regulate my temperature indoors or out. Lack of social engagements and general malaise made me slow to pull the flannels and wools from bins under my bed. I lingered in linen long into November. My nightly walks stuttered, then stopped. I turned up the space heater in my three-season porch and wore bike shorts under the desk, out of Zoom camera range. The view through my window was bare branches, gray skies. I added a blanket onto my lap, tucked my feet into slippers, barely moved all day. There was no adjusting the thermostat for my visiting elderly parents. No cracking a window when the fireplace made the house too hot during dinner parties. No warming up the car to drop off school kids when it was too cold to walk. Car-to-store and store-to-car barely warranted a hat, let alone mittens. I hid inside. It snowed. I was so focused on the losses that the cold simply became a burden on top of other burdens. Hand washing, social distancing, and masking were this year’s winter layers.

* * *

After a year of stillness, the sculpture was movement and dance, passage and becoming. I began visiting first thing in the morning, at noon and after dark, gaining strength every time. Every day was a new invitation to walk through winter, to pass through solitude. I met neighbors making their own pilgrimages. The coldest temperatures of the winter were no longer holding us indoors.

Beyond the thing-ness of the sculpture was the story. It was an ice curtain beckoning me to slough off layers of stagnation, desperation. To pass through into mystery. Into plot twists. Into rising action and climax. To cross into a world where I left my house and entered the woods. Where I might meet a wolf or a woodsman or a witch. I took a step and crossed through.

Photos by Mahadev Dovre Wudali